This is an article on the contemporary Pagan community in England and Wales, based on what the census results can tell us.

How many Pagans are there? Where do they live? What do they look like when broken down by age and sex?

What is a Pagan?

Pagans are difficult to count, for several reasons.

The first problem is that there is no universally agreed definition of what a Pagan is. This means that it is sometimes difficult to determine which answers to the religion question on the census should be put into the ‘Pagan’ bucket.

In the modern context, ‘Paganism’ is an umbrella term. There are certain traditions – the witch religion of Wicca, for example, and the Norse movement known as Asatru – which everyone agrees are Pagan. Other cases are more uncertain. What about Druid revivalists, for example? Most modern Druids are Pagans, but by no means all. The then Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, became a Druid of Gorsedd Cymru in 2002. What about Thelema, the movement founded by Aleister Crowley? What about people who follow reconstructed pre-Christian polytheistic traditions but decline the term ‘Pagan’?

There are other ambiguities too. Many people who describe themselves as ‘animists’, or ‘shamans’, or ‘pantheists’ may meet popular and academic definitions of Pagans (and may regard themselves as such). But many other people who use the same labels may not.

At the time of the 2001 census, the main British Pagan umbrella group, the Pagan Federation, tried to deal with the problems here by encouraging its supporters to write simply ‘Pagan’ on the form. But it is not clear how many Pagans followed this advice (or even heard about it). The PF made the same recommendation in 2021. In 2011, it took a slightly different line and recommended that people write ‘Pagan –’ followed by their individual tradition (the so-called ‘Pagan Dash’ approach).

Even if all Pagans could be got to write the same thing on the census, that would not mean an end to the problems. There is reason to believe that some amateur comedians describe themselves as ‘Pagan’ as a means of identifying as nonreligious or atheist. The same is true of ‘Heathen’.

Finally, there are strong grounds to believe that many Pagans do not declare their religious affiliation – using whatever term – on the census. We will come back to this.

The census figures

National censuses have been taken in Britain since 1801. The idea of asking people about their religion was debated in the nineteenth century, but it was controversial and never implemented – although in 1851 a census of places of worship (not individual worshippers) was undertaken.

In 2001, a question on religion was finally included, although answering it was not made compulsory.

By this time, there was an established Pagan community in Britain. The contemporary Pagan revival in this country began in earnest in the decades following World War II, and Paganism could be regarded as a mass movement by the end of the century. By then, the movement had caught the attention of people in wider society, and in the latter part of the 1990s there were several unofficial attempts to estimate the number of Pagans in Britain. These estimates converged on the range of 107,000 to 140,000. [These estimates were covered in the first edition of Ronald Hutton’s magisterial work The Triumph of the Moon (1999), but they were dropped from the second (2019) edition. They included Pagans in Scotland – the data in this article otherwise relates only to England and Wales.]

When the 2001 census results were published, a somewhat different picture seemed to emerge. The religion question threw up the following figures for ‘Pagan’ and other answers that might plausibly be bracketed with it:

Asatru – 93

Celtic Pagan – 508

Druidism – 1,657

Pagan – 30,569

Wicca – 7,227

The numbers above add up to 40,054 – considerably less than the estimates from the 1990s. How do we explain this discrepancy?

The census figures are almost certainly undercounts. There are a number of reasons why only a fraction of Pagans in England and Wales would identify themselves as such in the census. As noted, the religion question is voluntary – and some people don’t bother filling in the census at all. Followers of unusual religions might have a particular reason for not wanting to record their adherence in state records. This problem was likely to have been particularly pronounced in 2001, when memories of the Satanic Panic were still vivid. People who were not deterred by this might still not want to answer the question. Some might not even regard their ‘Pagan’ beliefs or practices as a religion.

Fast forward 10 years. In the 2011 census, many more Pagans appeared than in 2001 – but again, many fewer than might have been expected:

Druid – 4,189

Pagan – 56,620

Reconstructionist – 251

Thelemite – 184

Wicca – 11,766

These numbers add up to 73,010. An interesting question is how many of the ‘extra’ Pagans in 2011 were people who had converted since 2001, as opposed to being people who had simply not declared their affiliation the previous time round.

The numbers rose again in the 2021 returns:

Druid – 2,490

Pagan – 73,733

Reconstructionist – 742

Thelemite – 227

Wicca – 12,813

These figures add up to 90,005. It is very likely that this is still an undercount. The true number of Pagans in England and Wales must be in the hundreds of thousands. Indeed, it is plausible that the Pagan community by now outnumbers the Jewish community (287,000), although it probably falls some way short of the Hindu community (1 million).

Pagan places

The next question that I’d like to look is where Pagans in Britain tend to live.

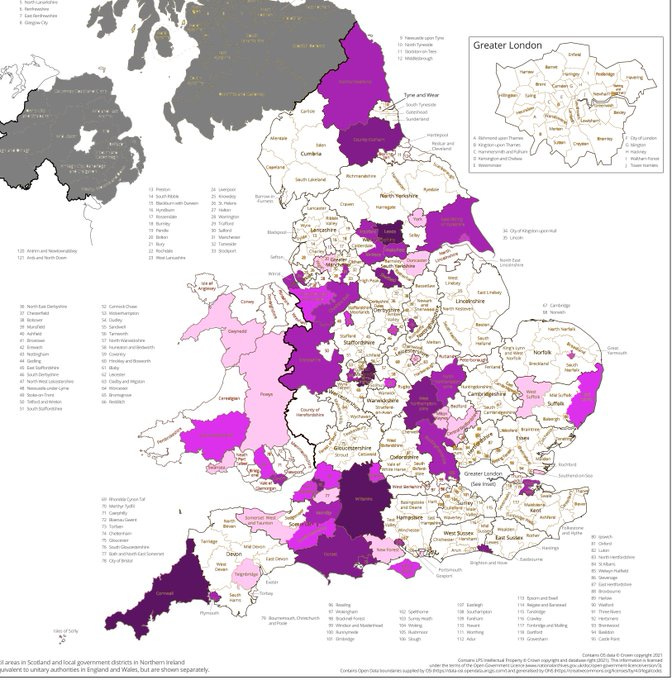

When the 2021 census results came out, I made a couple of rough-and-ready maps for this purpose. I counted everyone who gave the answers ‘Pagan’, ‘Wiccan’, ‘Druid’ or ‘Thelemite’.

The first map shows absolute numbers:

There are some unexpected results here. Durham and Leeds are well represented, perhaps because they are university cities (although Oxford and Cambridge don’t do well). Wiltshire is surprisingly Pagan, as is west Northamptonshire. It is less surprising that many Pagans show up in Cornwall, Brighton and Birmingham (albeit for different reasons in each case).

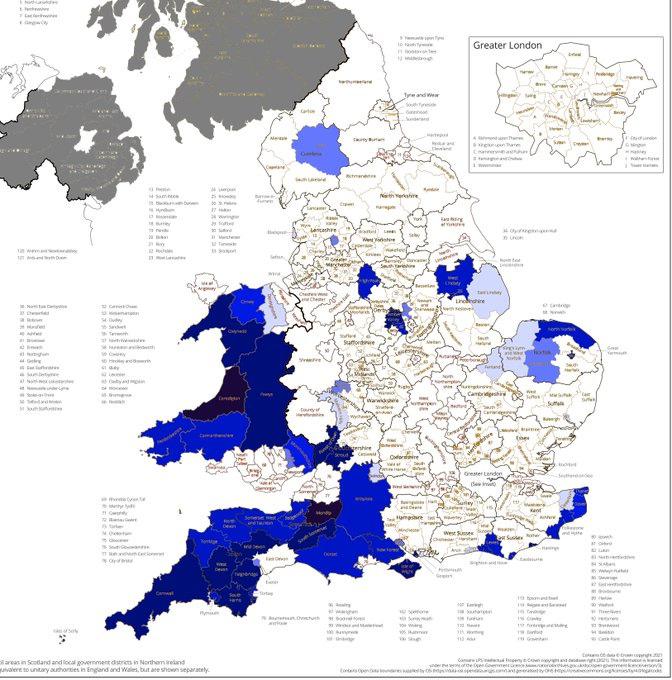

The next map shows numbers relative to total population:

This paints a somewhat (but not totally) different picture. It seems that Pagans are particularly concentrated in the West County and in Wales (with the notable exception of Glamorgan). There are unusual concentrations elsewhere, including Derbyshire and Lincolnshire.

Unfortunately, the maps don’t really work at showing the Pagan presence in London because London is divided into numerous boroughs, none of which has a particularly strong Pagan presence.

Age and sex

Most Pagans who are willing to declare themselves as such on the census form are women. In the 2021 results, 62% of people who wrote in ‘Pagan’ (45,695) were female and 38% (28,040) were male. For those who wrote not ‘Pagan’ but ‘Wiccan’, the disparity rose to 78% against 22%. Lest anyone attribute this to a half-baked theory that wOmEN aRE MoRe spIRItuAL, the disparity among people who identified as adherents of other religions was low to non-existent: 55/45% for Christianity, 49/51% for Islam and 50/50% for Hinduism.

Interestingly, the sex division has grown over time. In the 2011 census, of the 76,136 people who gave broadly Pagan-type answers, 57% were women (43,108) and 43% (33,028) were men.

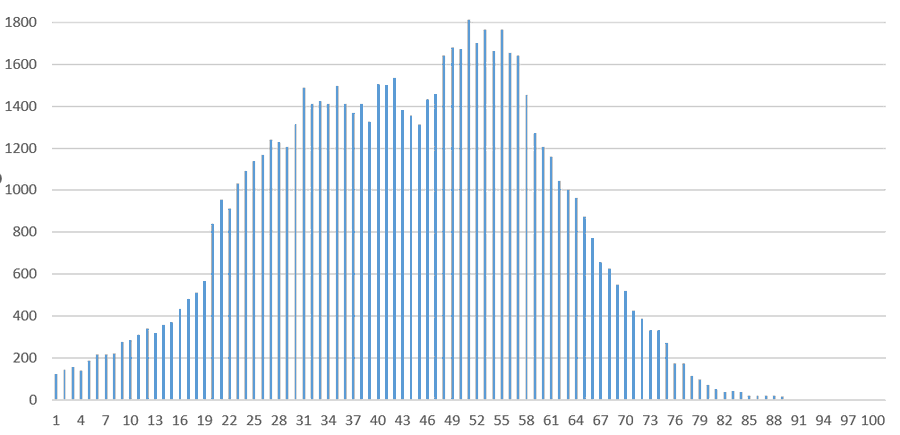

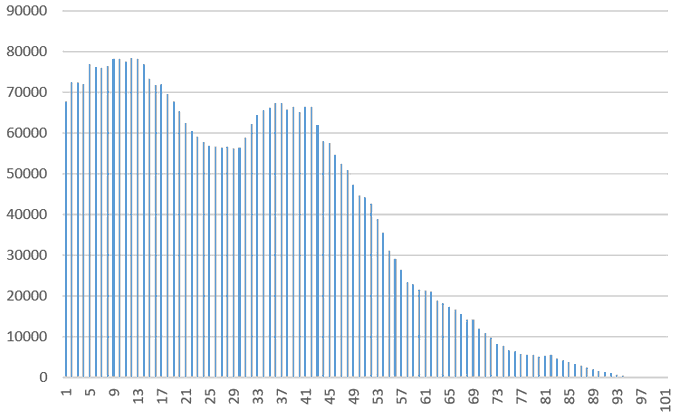

As to age, there are relatively few minors in the Pagan community. It is largely a religion – as we know – of adult converts. The ages of adherents peak around the 50s:

In other religions, the patterns are different. Christianity is an ageing religion, with later peaks, but it still has a significant proportion of minor members:

Islam, by contrast, is a religion shaped by birthrates and immigration. It has many minor members, and an adult peak around the late 30s and early 40s:

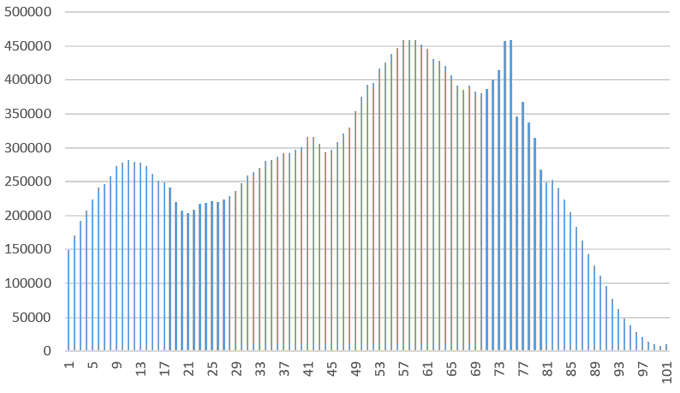

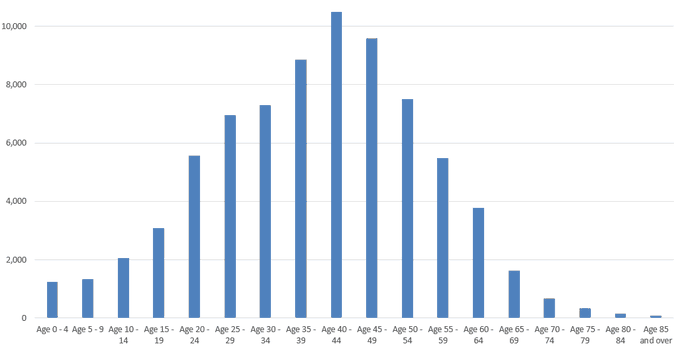

As to the age breakdown of the Pagan community, there is an interesting difference between the 2021 results and the 2011 results. This is the data from 2011 (illustrated in a less granular way, so the picture is clearer):

Essentially, what happened between 2011 and 2021 is that the age peak moved forward 10 years, from the 40s to the 50s.

What this means is that Paganism appears to be an ageing religion. Is it therefore headed for decline?