In recent times, there seems to have been growing interest in the ancient Greek mystical tradition known as Orphism.

This interest is evident in the academic world, with the appearance of studies such as Daniel Malamis’ The Orphic Hymns.* It has broken through into popular culture, with the Netflix series KAOS featuring Orphic themes prominently. It is also evident among practitioners of modern revived paganism.

[* = This book is based on Malamis’ PhD thesis, which is available free here.]

In modern pagan circles, the Orphic revival has attracted some quite different people. At one end of the spectrum, we find some genuinely fascinating engagements with the Orphic material by modern mystics like Kristin Mathis, as well as an accessible introduction written by Tamra Lucid and Ronnie Pontiac. At the other end of the scale, there are dickheads like this:

Recently a visitor [to Corfu], a supposed devotee of Orpheus who develops performances and practices based on what they call “Orphism,” asked me to read a street sign for them, saying: “I can read Greek letters, but it’s just Modern Greek, isn’t it, so nothing like ‘real’ Greek.” The street sign simply featured place names… [Reference: Sasha Chaitow’s Substack]

What was Orphism?

We’re not entirely sure. There are limits to how much we can say about the Orphic movement, for a couple of reasons.

The first reason is that Orphism was a secret cult. It did not seek to publicise its teachings and practices. It was esoteric in the literal sense of being a movement for initiated insiders. It is significant that the phrase “shut the doors” seems to have recurred in Orphic texts. It is likely that this originally referred to the Orphics literally carrying out their rites behind closed doors; it later became a more general metaphor for secrecy. These people didn’t make it easy for inquisitive scholars living thousands of years later to work out what they were up to.

What we can say is that Orphism had distinctive beliefs and practices which stood to some extent apart from the religious mainstream. It was a minority movement within ancient Greek culture: a way of interacting with the divine which was quite different from that of the marble temples and state festivals. Orphism was not opposed to traditional mainstream paganism, like Christianity was – Orphic initiates probably continued to participate in the traditional observances as far as they could – but it did amount to a different style of being religious.

Another problem is that Orphism was not a single unified system. It was a loose collection of groups and practitioners whose rituals and beliefs would have evolved considerably over a period of centuries. Some scholars, known as ‘Orpheo-sceptics’, would go so far as to deny that there was a coherent thing that can be called an Orphic movement at all.* This probably goes too far. But it is fair to say that we are not talking about an organised religion with a standardised set of texts and creeds. To that extent, saying things like “the Orphics believed…” is always more or less hazardous.

[* = This is the position of Radcliffe Edmonds, who invented the term ‘Orpheo-sceptics’ and is perhaps the leading scholar of Orphism writing in English today. The study of Orphism is not, incidentally, a good field for monoglot English-speakers: serious research requires a knowledge of several other modern languages, notably French.]

Who was Orpheus?

The Orphics were named after Orpheus, who is one of the best-known characters from Greek mythology – a marvellous poet and musician who could charm animals, trees and even stones with his lute or lyre. He was seen as a semi-divine figure. His father may have been Apollo, the patron god of music, and his mother may have been Calliope, one of the art goddesses known as the Muses. Orpheus has been the subject of numerous works of art through the centuries. In KAOS, he is portrayed as a rock star.

The most famous story told about Orpheus is that he made a journey into the Underworld while still alive in order to rescue his deceased wife Eurydice. Through his music, he won over the powers of the Underworld and obtained her release. The best-known version of the myth ends in tragedy as Orpheus subsequently loses Eurydice because he looks back at her on the return journey before they reach the land of the living. It is a powerful and memorable story – although the part where Orpheus looks back does not appear until quite a late stage, in the work of the Roman-era poet Virgil.

The evidence

As will be clear from what we have said so far, we don’t have much to go on when we try to reconstruct who the Orphics were. Orphism is an obscure subject even among scholars. You can study ancient Greek history and literature to postgraduate level and come across little or nothing about the movement (in the same way as you can take a degree in, say, American Studies and hear little or nothing about the Jehovah’s Witnesses).

A careful reading of the canonical texts from the so-called classical period of Greek history – roughly, the 400s and 300s BCE – will yield a few references to Orphism. These references confirm that there were people living in Greece at that time who regarded themselves as followers of Orpheus. It appears that they went through initiation rites; that they had an attachment to the god Dionysus; and that they lived an unusual lifestyle which involved a vegetarian diet and other practices relating to purity.

The most illuminating source from the classical period – although he is not very illuminating – is the philosopher Plato. What he says is interesting because it appears to reveal why the Orphics did what they did. It seems that they believed that human souls are incarnated in physical bodies as a punishment, and that becoming an Orphic initiate was the ticket to a blessed afterlife. In this context, it is probably no coincidence that Orpheus was known for crossing the boundary between life and death, and for seeking to rescue his wife from the Underworld.

Plato seems to have emerged from the same broad tradition of thought as the Orphics, but he didn’t like them very much. He thought that Orphic initiators were charlatans who tried to make money out of rich dupes. And indeed there is some evidence that financial and sexual exploitation existed in these circles; such problems are unfortunately to be found in every religious tradition.

Archaeological evidence can shed a certain amount of further light on the subject. One of the earliest relevant finds is a piece of bone from Olbia – a Greek colony in modern-day Ukraine – which dates from the fifth century BCE. This is inscribed with (amongst other things) letters that spell out “Orphic…”. Exactly what we should make of this item is unclear.

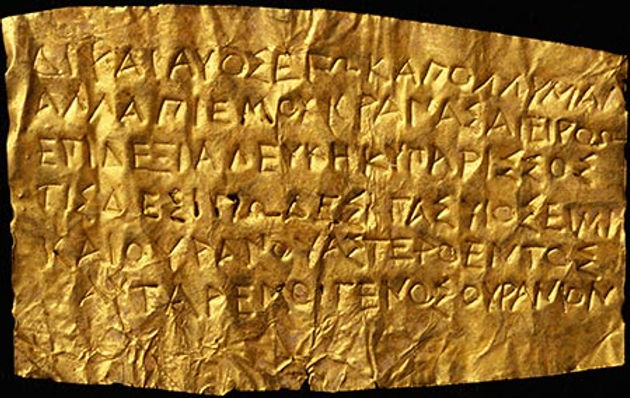

From roughly the fourth century BCE onwards, a more substantial body of archaeological evidence becomes available to us. This consists of pieces of gold foil with poetic texts inscribed on them – the so-called ‘Orphic gold tablets’ or ‘gold leaves’. The gold leaves were found in graves, usually belonging to women. The texts written on them differ among themselves, although there are certain common themes. Most scholars accept that the leaves have something to do with the Orphic movement. Notably, they refer to relatively obscure gods (Phanes, Protogonos) who are known to have been of interest to the Orphics. The leaves don’t mention Orpheus, although they do mention Dionysus, and in certain cases they are shaped like ivy, the plant of Dionysus.

The leaves refer to known Orphic themes, including purity and initiation. They describe the Orphic initiate as being part-human and part-divine: “a child of earth and starry heaven”. The initiate’s goal was to transcend their mortality and enter into divinity: “you have become a god from a human”. As the finding places of the leaves suggest, this divine salvation was to be found in the afterlife. In some of the leaves, the dead person was given instructions for what to do when they got to the Underworld. They were to drink from the water of a particular lake, and to say certain words to the guards there.

By way of example, the following text comes from a tablet found in the grave of a young woman who died around 400 BCE in Hipponion in modern-day Italy:

….When she shall die

and go to Hades’ well-built palace: there is a spring

on the right, and by it stands a white cypress.

There the souls of the dead cool themselves when they descend.

Do not approach or go near to this spring,

but move on, and you will find the lake of Memory

and its cold water flowing forth. There are guards here,

and they will ask you with wise words what you are

looking for in the gloomy darkness of Hades.

Say: “I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven.

I am parched with thirst and failing. But quick, give me

cold water to drink from the lake of Memory.”

And they will show you to the King of the Underworld;

and they will let you drink from the lake of Memory;

and when you drink you will proceed on the holy path

that other famous initiates and Bacchics walk.

The final line points to the link between Orphism and the worship of Dionysus, also known as Bacchus. This link is worth dwelling on. Dionysus was, of course, the god of wine – and, more generally, the god of shifting identities, ecstasy and transgression. It may be significant that Dionysus journeyed to the Underworld to rescue his mother Semele, just as Orpheus did for Eurydice. Dionysian cult-groups or thiasoi were an established feature of Greek religion (and in due course of Roman religion). Is there perhaps a source of insight here? Can an examination of Dionysian cult practices provide clues about what the Orphics got up to when those doors were closed?

Only up to a point. We do know a certain amount about the cult of Dionysus, but we don’t know nearly as much as we would like to. Our best-known source is a tragic play, Euripides’ Bacchae, which presents initiates engaging in homicide and cannibalism. But this is a fictional work by a notoriously provocative radical playwright. What happened in real-life thiasoi is imperfectly understood. The rites seem to have involved drinking, dancing, music, singing, and wearing animal skins. They often seem to have taken place at night and in wild, marginal places: caves and mountains. They were sometimes restricted to women. Some of these things may also have been true of Orphic observances. Interestingly, one source mentions that Dionysian rites involved smearing clay-soil and bran on initiates and then wiping them off. Perhaps this was thought to remove spiritual pollution. The newly-purified initiates declared: “I have escaped the bad, I have found the better”. This is the sort of thing that Orphic initiates would plausibly have done.

So much for the evidence for Orphism in the classical period.* The movement continued for a period of centuries – with goodness knows what changes – and in later times we find the only extended surviving Orphic text, a collection of poems known as the Orphic Hymns. We will come back to this later. Orphic ideas are also preserved in the writings of philosophers of the Neoplatonic school, who were descendants of the Orphic tradition via their founding figure Plato.

[* = This is not a comprehensive analysis of the evidence. You’ll have to buy my forthcoming book if you want to know more.]

We might note at this point that there is an interesting tension that emerges from the evidence. On the one hand, the Orphics seem to have been adherents of the variety of spirituality that emphasises purity and seeks to escape from the earth-bound human condition. On the other hand, they worshipped the orgiastic god Dionysus, the wildest deity of the Greek pantheon. In the same vein, Plato reports that the Orphics’ observances included “pleasures and festivals” and “pleasant games”. Orphic initiates were therefore poised between two modes of engagement with the divine. They were at once monks and hippies – to use terms which are admittedly broad and anachronistic.

How do we reconcile these different styles of religiosity? Do we need to reconcile them? Perhaps they are complementary ways of achieving transcendence.

How did Orphism get going?

The evidence suggests that the Orphic movement originated in the sixth century BCE. Our first evidence turns up in the fifth century; and there is no trace of Orphism in the poems of Homer and Hesiod, which probably date from the seventh or early sixth centuries.

This dating is consistent with the fact that Orpheus himself first appears as a mythological character in the sixth century, when he is depicted on a sculpture from Delphi and mentioned by the poet Ibycus.

As to where Orphism came from, this remains unknown. Some scholars have suggested that the movement originated at the edge of the Greek world or beyond it: Orphic ideas have been traced to Egypt, Phoenicia and India. At one time, it was fashionable to derive Orphism from the shamanic practices of Central Asia.* Funnily enough, ancient Greeks may have thought along similar lines. Both Orpheus and Dionysus were presented in myth as journeying into the heartland of Greece from outside. But this was probably just a symbolic way of emphasising their otherness. In all likelihood, Orphism was Greek.

[* = The term ‘shamanism’ is far too widely used, in my view. It really only applies to the religious practices of the Tungusic people of Siberia. The over-use of the term is due in large part to the twentieth-century scholar Mircea Eliade, although it goes back a lot longer than him.]

The movement seems to have had a particular connection with the Greek colonies in southern Italy and Sicily – ‘Magna Graecia’, or Greater Greece. The gold leaves seem to have originated in Magna Graecia. We also, for example, have vases from Apulia in south-eastern Italy which depict Orpheus and Dionysus in contexts that seemingly relate to the salvation of initiates and the afterlife.

Doctrines – Reincarnation

We may now move on to look more closely at certain specific ideas that the Orphics seem to have believed in.

The first of these is reincarnation, or metempsychosis in Greek. We have noted that incarnation in the human body seems to have been seen as something negative in Orphic circles: something from which to escape. It appears that this idea could be elaborated into a belief that we undergo repeated cycles of incarnation until we find release.

The caveat applies that we can’t know if all Orphics believed in reincarnation. But it looks like at least some did.

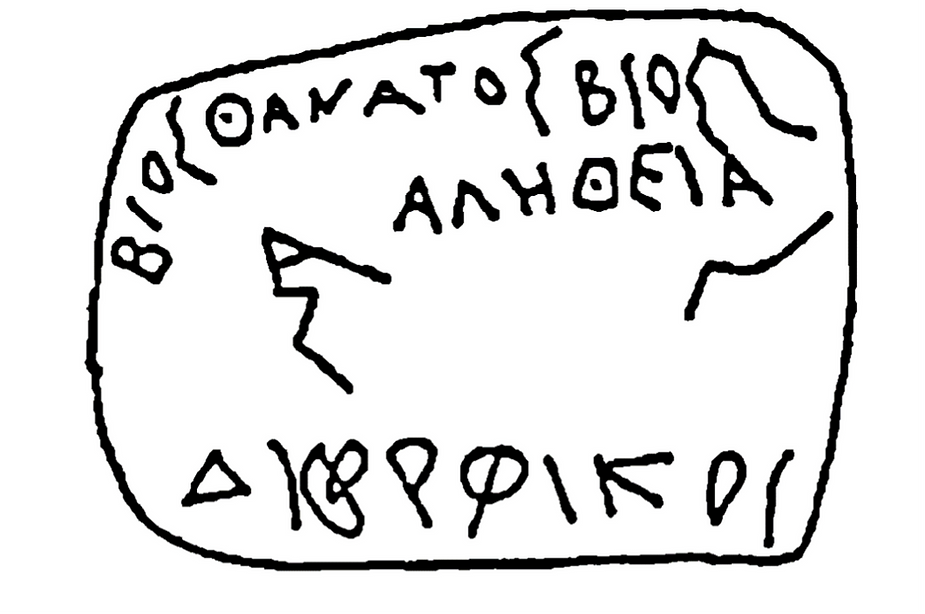

There are possible enigmatic references to reincarnation in early Orphic texts. The piece of bone from Olbia that we referred to above contains the words “life death life” (bios thanatos bios). This may be a reference to reincarnation from one life to another; although equally it might mean something totally different. One of the gold leaves refers to escaping a “cycle”. Given that the leaf was found in a grave, this can plausibly be interpreted as meaning escape from a cycle of incarnations. Again, however, this is open to debate.

We can be more confident in saying that beliefs in reincarnation were found among people and movements which were adjacent to Orphism and drew on the same pool of ideas – the cult of Dionysus, the aristocratic poet Pindar, the esoteric philosophical school of Pythagoras. If these people believed in reincarnation, the Orphics probably did so too. But we cannot be certain. You see how difficult it is to pin these things down.

Readers will probably be wondering at this point about the relationship between these early Greek beliefs in reincarnation and equivalent ideas in South Asian religions. There is a history of bafflement among scholars over who influenced whom. Perhaps the similarity is just a coincidence.

Doctrines – The Zagreus myth

Another specific belief of the Orphics that we can tentatively reconstruct is what has been called the ‘Zagreus myth’. This goes roughly as follows. The gods were ruled over by a series of kings, with one generation succeeding another. The first king, Ouranos (Heaven) was succeeded by his son Kronos; and Kronos was succeeded by his own son Zeus. Zeus in turn chose as his successor the god Dionysus, whom he had fathered with the Underworld goddess Persephone. The Titans, an older generation of gods, became jealous and plotted against the young Dionysus. They lured him away from his guardians, dismembered him and ate him. Enraged at this crime, Zeus incinerated the Titans with a thunderbolt; and human beings were formed from the ashes. Meanwhile, Dionysus was restored to life, perhaps with the help of Demeter, or Athena, or Apollo. Dionysus seems to have been known in this context by the title of ‘Zagreus’, Great Hunter.

Because humans were formed from the ashes of the Titans, who had eaten Dionysus, we contain within us elements both of the Titans and of Dionysus. So we are partly divine, but also tainted by sin. As we have noted, the idea that we are in need of being purified from sin is one that we also find in other Orphic contexts. It appears in Plato; and the gold leaves likewise contain references to to paying the price for wrongful deeds and becoming free from punishment.

This all seems to give us a useful insight into the Orphic view of the human condition. But a couple of cautions are needed. The first is that the Zagreus myth is only imperfectly attested in the ancient sources. Many adherents of the Orphic movement probably did come to believe something along the lines of the above. But it is difficult to find clear early evidence to this effect. We can be broadly more confident from the 200s BCE onwards, but before that we have only scraps of equivocal data. The myth may have been a relatively late addition to Orphic theology. Plus there is the inevitable caveat that Orphism was not a uniform movement, so it is difficult to make generalising statements to the effect that the Orphics believed in the Zagreus myth, in the conception of humanity associated with it, or indeed in anything else.

The second reason for caution arises from the fact that the Zagreus myth looks a bit like the Christian doctrine of Original Sin – the idea that human beings have inherited an essential sinfulness from Adam, and that we are therefore in need a saviour in the form of Jesus Christ. Other parallels too can be drawn between Orphism and Christianity. If you squint a bit, the murder and rebirth of Dionysus can start to look a bit like the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus. Some scholars have got altogether carried away with this sort of thing, arguing that there was a direct, lineal connection between the Orphic movement and the theology of the Christian church. On this view, Orphism was a Christianity before Christ. Theories of this sort were fashionable in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the notion became prevalent that Christianity was a kind of plagiarism of earlier Mediterranean mystery cults. The same idea survives in some online spaces today, where you can find dull-minded little men telling you triumphantly that Mithras was born on Christmas Day and so forth.

This sort of thing is misguided. There are similarities between Christianity on the one hand and Orphism and other ancient occult sects on the other. The ancient Eastern Mediterranean was unusually fertile in esoteric beliefs and practices – I have called it the ‘republic of Esoteria’ – and all of the movements just mentioned developed out of the stew of ideas that was bubbling in that place at that time. The writers of the New Testament and the Church Fathers drew on currents of mystical thought that were swirling around Esoteria, and it is not difficult to find influences from ancient occult movements in Christianity (particularly its Eastern Orthodox varieties). Yet we should not get carried away. The idea that the early Christian church is a rip-off of Orphism or other mystery cults is simplistic, and does not take account of the profound Jewish contribution to Christian theology and morality. In practice, it quickly degenerates into a kind of ‘gotcha!’ for Reddit Atheists who don’t care about the complex and fascinating world of ancient esotericism any more than they do about Jesus.

Doctrines – The divine as singular and plural

The Orphics seem to have had a distinctive conception of the divine as being at once singular and plural. This was neither ‘hard’ polytheism of the sort that seems to have characterised ancient popular religion; nor ‘hard’ monotheism in which there is one true god as opposed to many false gods.

This view of the divine formed part of a broader set of ideas that were found in ancient Greek thought to the effect that a single overarching divine power stood behind everything, including the gods. This supreme power was sometimes identified with Zeus, the chief god of the traditional pantheon. The kind of ‘soft’ monotheism that we are dealing with here is sometimes known as henotheism.*

[* = I don’t like the term ‘henotheism’, which originally had a different meaning. But it’s so widely used in religious studies that it’s appropriate for me to use it here.]

At this point, we must turn to look at the earliest extended piece of Orphic writing that is available to us. This rare and obscure text is preserved on a document known as the Derveni Papyrus, which is itself the oldest surviving manuscript from Europe. It was unknown until 1962, when roadbuilding works in a mountain pass in Greece unearthed a group of ancient graves. In one grave were found the carbonised remnants of the papyrus, which had been burned on the dead man’s funeral pyre but had escaped being entirely consumed by the flames.

The Derveni Papyrus dates from c. 340-320 BCE, but the text written on it is significantly older; and that text quotes parts of an earlier text, which may go back to the fifth century BCE. The earlier text seems to have been a theogony, or an account of the origin of the gods (the best-known example of this genre is Hesiod’s Theogony).

If you know about the Derveni Papyrus and you are wondering why I haven’t mentioned it until now, it’s because it isn’t a particularly useful source for our purposes. It has a few interesting pieces of information in it. It refers to mystery-initiates (mystai). It also alludes to punishments in Hades; and to making offerings to the spirits known as the Furies, who are identified as souls of the dead. These scraps of data are broadly consistent with what we otherwise know about Orphic beliefs. But the Papyrus doesn’t – in general – tell us very much about Orphic theology.

There is one major exception to this generalisation, and it is an important one. The theogony that is (partially) preserved in the Derveni Papyrus gives a place of special honour to Zeus. In particular, it contains the following lines:

Zeus of the flashing thunderbolt was born first, and Zeus last.

Zeus is the head, Zeus is the middle, from Zeus all things are made….

Zeus is king, Zeus of the flashing thunderbolt is chief of all.

This looks like a kind of hymn to Zeus. Indeed, the whole theogony may have been a hymn to Zeus. This glorification of the king of the gods was not an isolated, eccentric feature of one specific text. The lines quoted above appear to have had real resonance in Orphic circles: they were expanded and re-used by other Orphic writers in later times to build up an evolving version of the ‘hymn’. It looks like we have stumbled on evidence that can tell us something important about the Orphic movement.

Sadly, complete versions of the evolving Orphic ‘hymn’ to Zeus do not survive, so we are left with the task of piecing together scattered quotations found in non-Orphic writers. Here, for example, is one version of the ‘hymn’ which is preserved in a treatise attributed to Aristotle:

Zeus of the flashing thunderbolt was born first, and Zeus last.

Zeus is the head, Zeus is the middle, from Zeus all things come to be.

Zeus is the foundation of earth and starry heaven.

Zeus is manly, Zeus is the immortal bride.

Zeus is the breath of all, Zeus is the surge of unwearying fire.

Zeus is the root of the sea, Zeus is the sun and the moon.

Zeus is king, Zeus of the flashing thunderbolt is chief of all.

He hides all things away and brings them back again to the joyful

light, as his holy heart wills, accomplishing terrible things.

We seem to have here a kind of anthem of the Orphic movement, and it is one that strongly suggests that the Orphics were henotheists.

Evidence of Orphic henotheism may be found elsewhere too. Fragments of later Orphic poetry appear to bear witness to a theology that was centred on a supreme god who could be identified with Zeus, Dionysus and/or the sun god Helios. As one line of verse put it: “Zeus is one, Hades is one, Helios is one, Dionysus is one”.

It bears noting that Orphic henotheism was not exclusively male. In the Derveni Papyrus, we find a passage that appears to present the goddesses of the Greek pantheon as a single Great Goddess:

Gé [Earth] and Mother and Rhea and Hera are the same. She was called Gé by custom, and Mother because everything comes from her (Gé and Gaia according to different dialects). She was called Demeter, as in Gé Métér [Mother Earth], the one name being made from the two parts, as it was the same name. And this is said in the Hymns: “Demeter, Rhea, Gé, Mother, Hestia, Déió”.

These ‘Hymns’ no longer survive. But at this point we may make mention of another set of hymns from the Orphic movement which by chance have survived. We have already mentioned these latter hymns: they are the collection that goes by the name of the Orphic Hymns. In modern times, they have become a popular text among pagan revivalists.

The Orphic Hymns are a late text, by ancient standards: they are no older than the second or third century CE, and they may have been composed a couple of centuries after that. The collection consists of 87 hymns addressed to a range of different gods and divine powers, Dionysus being the most prominent among them. The Hymns seem to have come from an Orphic group that was based in what is now western Turkey.

The Orphic Hymns are the nearest thing that we have from the ancient world to a prayer book. The Dutch scholar Daniel Heinsius referred to them as “a true litany of Satan himself”. It is no surprise that modern pagans have adopted them as a liturgical text. They were first translated into English by one of the earliest modern pagan revivalists, Thomas Taylor. His translation feels dated now, although the register of English in which it is written is not dissimilar in feel to the Greek. Several new translations have appeared in recent years aimed specifically at modern pagans, including Patrick Dunn’s The Orphic Hymns.

The theology of the Orphic Hymns is one of simultaneous unity and diversity: there is a single supreme divine power which is refracted through the distinct personalities of the gods of the pantheon. The divine is both plural and singular.

The Hymns blur the boundaries between the numerous goddesses and gods of the pantheon. Different deities are identified with each other; and the same descriptive words and phrases recur repeatedly in hymns to different gods. Individual gods are addressed in all-encompassing terms – as the beginning and the end, male and female, creative and destructive – as if each of them partakes in the same divine essence.

The Orphic conception of the divine, then, can be seen as inhabiting a grey area between polytheism and monotheism. It is a theology of shifting, permeable boundaries; a subtle engagement with a transcendent and elusive divine reality.

Conclusion

Orphism is perhaps the earliest attested form of European mysticism.* We don’t know all that much about it, but what we do know is intriguing. We find in the surviving evidence a spirituality based on a fascinating combination of the ascetic and the ecstatic, as well as a fluid conception of the divine which hovers between monotheism and polytheism.

[* = This term is anachronistic, of course, but it’s still meaningful and useful.]

The Orphics will never lack people who are drawn to study them and to seek out what we can uncover of their beliefs and practices. The current revival of interest in the movement will no doubt wane; but we may hope that it will never lapse into obscurity. The Orphics, wherever they are now, deserve better than that.